Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic

Michael Jackson looks down at us from his seat on a magnificent stallion in the first gallery of the Seattle Art Museum’s stunning exhibition “Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic.” Looking closer we see subtle references to Jackson’s famously changing color: from rear to head, the horse actually changes color from brown to white and, in the sky, a white and a brown putto place a garland on his head. Wiley actually met with Jackson and the singer chose the Rubens equestrian portrait of Philip II of Spain as the basis for his portrait (in the original the horse is brown and includes voluptuous women with a globe in the sky). Wiley titled his painting “Equestrian Portrait of King Phillip II of Spain (Michael Jackson),” making his provocative purpose clear. The 16th -17th centuries were the height of colonization and the slave trade, so placing Michael Jackson in the seat of power of that time provides an intense contradiction and brilliant upending of history.

Kehinde Wiley characterizes black masculinity in our contemporary media culture as “structured, manufactured and consumed” to create a “conspicuous fraud.” He repositions black men and women from their traditional role in “grand manner” paintings as slaves or servants or in our media as victims or perpetrators of violence. In Kehinde Wiley’s paintings black people become heroes and saints. Most of his models are ordinary people, rather than celebrities, making the transformation all the more dramatic and pointed.

He embeds this driving purpose in painting and sculpture that overwhelms us with beauty, scale, and technical virtuosity. As he acknowledges the risk of aesthetics obscuring meaning, he encourages us to look beyond our first glance to the many understated jokes and surprises in the details of the work.

The artist jump shifts from one historical format to another, keeping us dazzled by his references, but disrupted by his reinterpretations.

Among the portraits, “Mugshot Study” 2006, based on a wanted poster the artist found in the street, stands out as a point of departure and foundation for the more elaborate works. Wiley here simply enhances a traditional mugshot, humanizing the young man with classical chiaroscuro. Under the portrait we see the assigned criminal number of the young man, almost invisible in white on white—a reference to who gave him the number and his status in a society that incarcerates millions of black men.

A roomful of “Religious Subjects” glow with gold leaf on small private altars, echoing the format of Hans Memling’s fifteenth century portraits of Flemish merchants. Here contemporary young black men hold emblems of power, their names declaring their identity.

Wiley began his project by finding volunteers in the streets of Harlem, what he calls “street casting,” although he presents only beautiful people (he also found models at a casting studio). Unlike for example, John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres’s plaster portraits of ordinary people in the barrio, Wiley’s focus is on physical beauty, even perfection, set in precisely quoted historical formats. If we are going to consume black men, he suggests, let us consume them as a supremely special experience based on elite status, rather than as criminals or victims or sports stars.

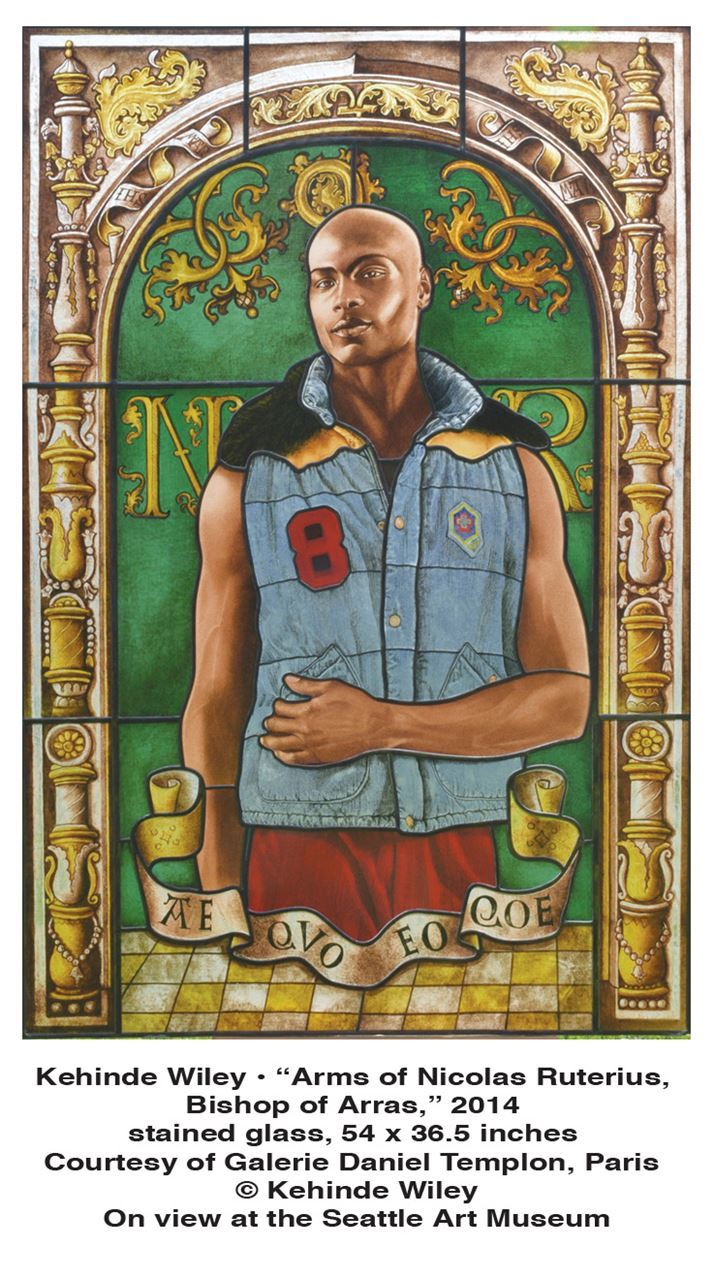

As we are bathed in the transparent colors of a room full of stained glass windows, beautiful black men as saints interrupt our expectations of religious clichés. These windows were created by skilled German artisans who have inherited the secrets of the centuries—old techniques of medieval stained glass windows, a format normally reserved for dead white saints.

Nearby, an alcove of small bronze portraits in the classical Jean Houdon style of idealized head truncated on a pedestal, features African and African Americans. Again interrupting an easy identification with an historical reference, the model for “Cameroon Study” had a shoe on his head. According to the artist, he based it on a shoe seller who balanced a shoe on his head as a way to advertise his wares. Such a surprise is vintage Wiley: a classical format tilts in a new direction.

Nearby, an alcove of small bronze portraits in the classical Jean Houdon style of idealized head truncated on a pedestal, features African and African Americans. Again interrupting an easy identification with an historical reference, the model for “Cameroon Study” had a shoe on his head. According to the artist, he based it on a shoe seller who balanced a shoe on his head as a way to advertise his wares. Such a surprise is vintage Wiley: a classical format tilts in a new direction.

Michael Jackson’s equestrian portrait belongs to the theme “Symbols of Power.” As a partner to that, Wiley created “An Economy of Grace,” portraits of women. Again he found random women to participate, but in this case they were elaborately adorned in Givenchy gowns, with sensational hair arrangements by the celebrity hair stylist Dee Trannybear. By far my favorite of the women’s portraits was “Judith and Holofernes” in which an imposing black Judith holds the white head of Holofernes (also a women) against a lush flower background. Wiley’s flower backgrounds have a way of wending their way in front of the figure, and most of them have metaphorical significance.

Aside from the triple bronze portrait “Bound,” of three women with huge braided hair intertwined, most of these portraits of women do not critique colonialism and its grand manner presumptions. Black women do not carry the same position as black men in our public media—we have Oprah for example. We think of black women as powerful, rather than as victims, as bearers of culture and home, as resistors to oppression, as fighters. Celebrity black fashion models date back several decades and Wiley’s insistence on lavish designer gowns and hair seemed to sit in that tradition, although perhaps the exaggeration of the hair and dress was itself a type of critique because it endowed these women as royalty not just objects of beauty.

Wiley’s painting and sculpture overwhelm us with their scale and meticulous detail (he works with a team in China these days). He floods us with sensory overload, then provokes us with the unexpected at every turn.

Susan Noye Platt, Ph.D.

Susan Noyes Platt, Ph.D., art historian, art critic, curator, activist, published “Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a Time of Crisis” in 2011 emphasizing activist artists in the first ten years of the 21st century. She continues to address politically engaged art on her blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com. As a curator, her focus is art about immigration, migration, and detention.

“Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic” is on view until May 8, Wednesday through Sunday at the Seattle Art Museum, located at 1300 First Avenue in Seattle, Washington. For more information, visit www.seattleartmuseum.org.